https://pin.it/1TfzNqXfq

The creation and refinement of the Japanese Zen Garden, or Karesansui (dry landscape), were not the work of a single individual at one moment in time, but rather an evolution shaped by philosophical shifts, religious practice, and notable artistic monks. While the style developed over centuries, the figure most closely associated with the early, definitive form of the karesansui is the monk Musō Soseki.

https://pin.it/24TEvrh4m

I. The Principal Architect: Musō Soseki

https://pin.it/75IBUSnjt

The creation of the Zen Garden as a distinct form of landscaping, integral to monastic practice, is largely credited to the celebrated Rinzai Zen Buddhist monk, poet, and calligrapher, Musō Soseki (1275–1351). He is often referred to as “The National Teacher” (Kokushi).The Garden as MeditationSoseki revolutionized garden design by consciously divorcing it from the traditional pleasure garden. His designs emphasized the use of stones and gravel over lush planting, transforming the garden into a minimalist, abstract space intended to aid in Zen meditation (Zazen). He viewed the process of design and maintenance as a spiritual discipline.

https://pin.it/5FlKsOZKK

His most famous surviving work, and a prototype for later Zen gardens, is at the Saihō-ji Temple in Kyoto, though it is now better known as the Moss Garden due to later transformation. However, his work at Tenryū-ji and his principles laid the philosophical groundwork for the karesansui aesthetic.

II. A Comprehensive History of the Zen Garden

The history of the Zen Garden is a narrative of spiritual importation, aristocratic aesthetics, and monastic refinement, spanning nearly a thousand years.

A. Early Influences (Nara and Heian Periods: 710–1185)

https://pin.it/1aDpyP6nJ

Long before the arrival of Zen Buddhism, Japanese gardens were already incorporating elements that would later define the karesansui.

●Shinto Purity: The use of white sand or gravel to represent a pure, sacred space, known as a niwa, was a practice derived from the native Shinto religion.

https://pin.it/5skhDvhk0

Chinese/Korean Models: Early gardens were often based on Chinese prototypes, featuring ponds and islands, reflecting the Taoist concept of the Islands of the Immortals (Horai-san). The first known gardening manual, the Sakuteiki (circa 11th century), provided detailed instructions for placing stones to avoid misfortune, establishing the deep, symbolic importance of rock arrangement.

https://pin.it/1vqQnufAN

B. The Zen Emergence (Kamakura Period: 1185–1333)

https://pin.it/3z4B1raXN

Zen Buddhism arrived in Japan from China, bringing with it a deep appreciation for simplicity, austerity, and a focus on direct, intuitive understanding (sudden enlightenment, or satori). The monks, particularly those of the Rinzai school, began building gardens on temple grounds, but space was often limited. This necessity was the mother of invention, leading to the abstraction of nature.

C. The Golden Age of Karesansui

https://pin.it/1m1YjHdyR

This era saw the true flourishing of the dry landscape garden.

https://pin.it/7FQqfvrge

1.Musō Soseki’s Impact (14th Century): As detailed above, Soseki formalized the garden as a meditation aid, abstracting water and space.

2.Shogun Patronage: Powerful Shoguns, notably those of the Ashikaga clan, embraced Zen culture. Shogun Ashikaga Yoshimasa was a key patron, integrating Zen aesthetics into the Kitayama and Higashiyama culture.

3.Sōami (15th–16th Century): A renowned contemporary artist and aesthete, Sōami is often credited with the design of the famous dry garden at Daisen-in (part of Daitoku-ji Temple). He further refined the use of white sand to represent vast rivers and oceans, with strategically placed stones acting as boats or islands.

4.Ryōan-ji Temple Garden (Late 15th Century): This iconic, arguably most famous, Zen Garden epitomizes the form. It consists of fifteen moss-covered stones set in a sea of white gravel, arranged so that only fourteen stones are visible from any single viewing point—a profound metaphor for the incompleteness of human perception and the need for effort (seeking the missing stone/enlightenment). The designer of Ryōan-ji remains unknown, though theories point toward Sōami or a lesser-known monk.

https://pin.it/3rzwSmbwc

D.Refinement and Evolution (Edo Period Onward: 1603–Present)

While the peak of karesansui was the Muromachi period, later eras continued to maintain and refine the tradition. The Edo period saw the rise of large strolling gardens, but the Zen temples preserved the dry landscape as a core element of their contemplative practice, cementing its place as an enduring symbol of Japanese culture.

III. Ten Lesser-Known Facts About the Zen Garden

1.The Viewer’s Role is Crucial: Zen Gardens are not meant for walking through (unlike strolling gardens, or chisen kaiyūshiki). They are specifically designed to be viewed from a fixed point, such as the veranda of the Hōjō (the head priest’s residence), forcing the viewer into a static position conducive to meditation.

https://pin.it/7kfPESmfY

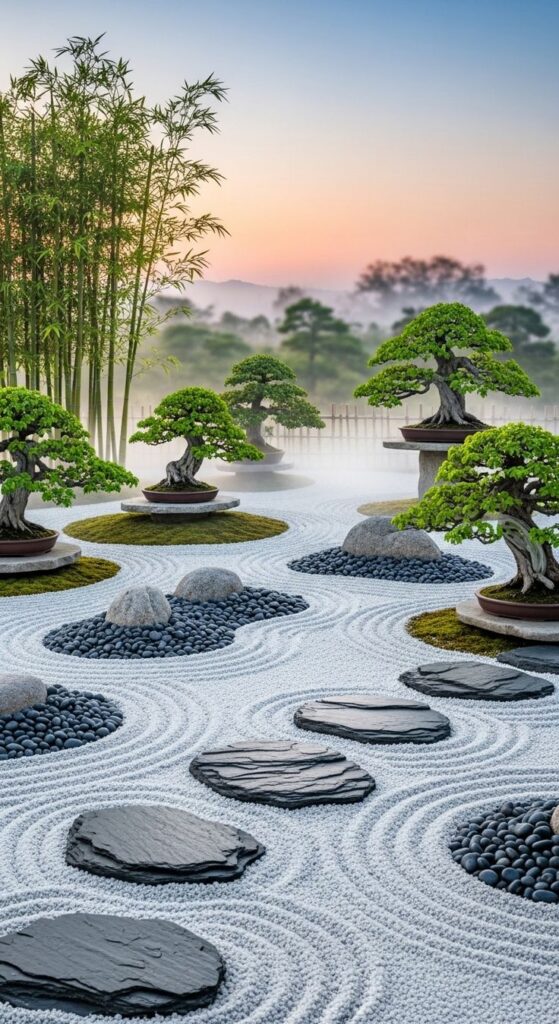

2.Raking is a Spiritual Act: The act of raking the gravel, creating the wave patterns (sui-mon), is a meditative discipline known as Samu. It is considered an essential chore (practice) for the monks, akin to cleaning the mind.

3.Moss Represents Time: The moss that often grows on the stones and around the base of the elements is highly prized. It symbolizes age, tranquility, and the passage of time (sabi), grounding the garden in the deep history of its place

4.The “Ocean” is Purely Abstract: In the dry garden, the white gravel is known as “sand” (suna) or “river gravel” (shirakawa-suna), and it is the water. The patterns raked into it are purely symbolic representations of ripples, currents, or waves; the mind must complete the illusion.

5.The True Scale is Cosmic: A small karesansui is designed to represent the entire cosmos (or a vast landscape of mountains and oceans) in a few square meters, embodying the Zen concept of “infinitude in a grain of sand.”

6.The Rock Arrangement is Based on Triads: Many important rock groupings are arranged in groups of three (sanzon-seki), a reference to the Buddhist Trinity (Maha-Kashyapa, Buddha, and Ananda) or the three main rocks representing the Buddha and two accompanying Bodhisattvas.

https://pin.it/dqTr64uhu

7.Kyoto’s Ryōan-ji May be a Literal Riddle: The 15 stones at Ryōan-ji are often theorized to spell out hidden Japanese or Chinese characters (e.g., the character for “heart” or “mind,” 心), though this is debated by scholars.

8.It’s Designed for a Climate of Scarcity: The karesansui style was partly a practical solution in areas where water was scarce or where the soil was too poor for elaborate planting, forcing the garden designer to rely on non-living elements.

9.Stepping Stones Tell a Story: When stepping stones (tobi-ishi) are used (usually outside the main raked area), their placement is specifically designed to control the viewer’s pace and gaze, ensuring they pause at key vantage points or focus on a particular element.

https://pin.it/exDP7xTqX

10.The Garden Walls are Essential: The simple, often plain earthen walls surrounding the Zen Garden are critical. They create a deliberate sense of seclusion and enclosure, acting as a boundary that shuts out the chaos of the outside world and focuses the mind entirely on the spiritual abstraction within.

I’m a professional Astrologer, Numerologist, and Gemologist, and also a passionate lifestyle blogger at CoonteeWorld.com — writing about fashion, travel, wine, horses, and the art of living.