The Vitis (grapevine)Revolution: A Comprehensive History of Wine, Myth, and Sanctification

Prehistoric Genesis:

From Wild Ferment to Cultivated Civilization

H3: The Wild Vine and Neolithic Domestication

The history of wine is intrinsically linked to the domestication of the Eurasian grapevine, Vitis vinifera ssp sylvestris, which grows naturally across a wide area encompassing Western Asia, the Caucasus, Central Europe, and the Mediterranean basin.

This wild vine provided the genetic material for the cultivated species, Vitis vinifera ssp sativa.

Archaeological and genetic studies indicate that the process of domestication during the Neolithic period occurred in at least two major centers:- the Anatolian Peninsula/Caucasus in the East and a less defined region in the West, potentially Spain.

The earliest definitive evidence of controlled winemaking stems from the Near East, confirming that the Caucasus and Zagros Mountains served as the primary cradle of viticulture.

Previously, the earliest evidence was traced to the early Neolithic village of Hajji Firuz Tepe in the Zagros Mountains of Iran, dated to approximately 5,400–5,000 BC.

Further discoveries from Godin Tepe in the nearby Middle Zagros Mountains established evidence dated to 5,100 years ago.

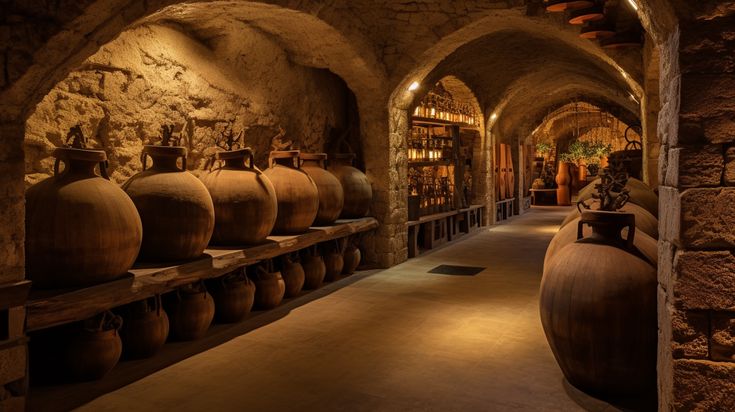

Subsequent breakthroughs occurred with the discovery of numerous underground jars and desiccated grapevine wood in caves at Areni, Armenia.

The presence of specialized storage vessels and organic residues from such early dates confirms that the technological basis for controlled winemaking—including fermentation management, storage, and aging—was established during the Neolithic era, making this complex innovation almost as old as organized agriculture itself.

caption: Wine, Prehistoric_Georgia. 8,000 years old vintage/Pinterest. com

https://pin.it/7BvHH6vCK

Early Centers of Production: The Fertile Crescent and Caucasus

As civilization advanced into the Bronze Age, wine transitioned rapidly from a presumed local Neolithic ferment to a highly valuable, structured commodity. Wine held a critical role in the emergence of the Bronze Age civilizations of the Fertile Crescent, including the Sumerians, Akkadians, Assyrians, and Babylonians.

The geographical proximity of the Caucasus established early trade routes. Armenian wine, for example, was an important trade product exported to Babylon and Mesopotamia starting at least in the 3rd millennium BC. This trade was conducted through sophisticated logistics, utilizing waterways like the Euphrates and Tigris rivers or overland routes through the Zagros Mountains. By the beginning of the 2nd millennium BC, the Mesopotamian city-state of Mari controlled the regional wine trade, transporting red and white wines in immense storage vessels called našpakum (roughly 3000 L) downriver to profitable markets, including Babylon.

The high cost associated with viticulture, transportation, and safe storage immediately transformed wine into an item of social stratification and power.

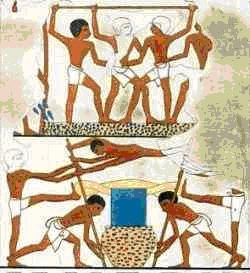

For the Hittites during the Late Bronze Age, wine (wiyana-) was apparently reserved for royal consumption and the elite, serving crucial religious functions such as libations and supplications to the diverse pantheon, while beer was the typical beverage of the lower classes. Similarly, in ancient Egypt, winemaking was established by early Canaanite settlers around 3000 BC, supplying the Pharaohs in a region where vines were not native.

https://pin.it/22eGkPtho

The consumption of wine was chiefly limited to the royal family and higher ranks of society. Wine also became deeply symbolic: in the Old Kingdom Pyramid Texts, the god Osiris was explicitly called “The Lord of the wine,” with the grapevine symbolizing his resurrection. This structural division—wine for the elite, beer for the masses—underscores how early wine production solidified and maintained Bronze Age social hierarchies.

Wine as a Vector of Civilization: Diffusion Across the Ancient World

The Phoenician Maritime Trade and Hellenic Expansion

The expansion of wine culture across the Mediterranean basin was fundamentally driven by maritime commerce and cultural exchange. The Phoenicians, whose civilization was centered in modern-day Lebanon, played a foundational role in this diffusion.

Between 1550 BC and 300 BC, their vast trading network spread from the Levant to North Africa, the Greek Isles, Sicily, and the Iberian Peninsula.

The Phoenicians were not merely wine shippers; they were agents of agronomy. They spread not only their famed alphabet but also their specialized knowledge of viticulture and winemaking, including the propagation of crucial ancestral varieties of Vitis vinifera. Through their trade, they either introduced or encouraged the dissemination of viticulture to modern wine-producing regions like Italy, Spain, France, and Portugal.

The influence of the Phoenicians and their Punic descendants in Carthage directly shaped the growing wine cultures of the Greeks and Romans. This transition from simple commerce to systematic agronomy is documented in the agricultural treatises of the Carthaginian writer Mago. Although the originals are lost, quotations preserved by later Greek and Roman authors like Columella confirm that Phoenician experts were skilled in planning vineyards based on favorable topography and climate, such as identifying the ideal slope for grape growing.

https://pin.it/vN5vR4uDT/Slope land grape growing

This documentation marks a crucial step: the professional systematization of agricultural knowledge necessary to maintain a predictable, high-quality supply required by their extensive trade network.

The sheer value and necessity of the wine trade, alongside other goods, provided the foundational economic stimulus that drove the first major waves of Mediterranean maritime expansion.

Roman Viticulture and the Systemization of the Old World

https://pin.it/4QvmofqhB

https://pin.it/29GVvo8fU

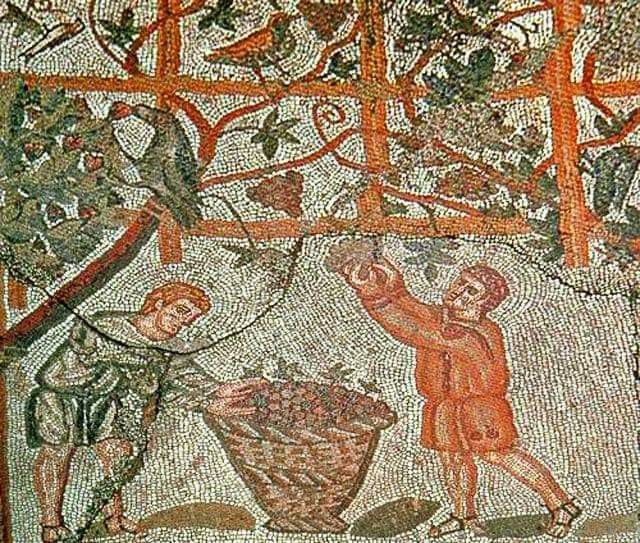

Grape cultivation reached Greece by the end of the 3rd millennium BCE and Italy around the start of the 1st millennium BCE. By the 8th century BCE, wine was deeply woven into the fabric of Greco-Roman society, serving as an essential daily energy source, a form of medicine, and a key marker of civilized culture.

Greco-Roman winemaking achieved a level of scientific expertise in vine-growing techniques and technology considered unmatched until the 19th century. While the Greeks understood the essential combination of soil, climate, and grape variety , the Romans were responsible for leaving behind the most comprehensive written descriptions of winemaking processes.

The high demand across all sectors of society led to a stratified market: premium vintages for the wealthy, ordinary wines for the masses, and cheaper drinks for the lower classes. This combination of the vine’s high productive potential, its low agronomic needs, and pervasive social demand cemented wine as a primary feature of the agrarian economy and a vital product of international trade, stabilizing and financing the growth of the vast empire.

Culturally, the consumption method often defined social status. The Greek practice of diluting wine with water during intellectual and social gatherings (the Symposium) served as a cultural control mechanism, managing intoxication to maintain intellectual discourse and symbolizing the ideal of moderation

This practice was noted as scandalous by others, such as the Macedonians, who preferred to drink wine “clean and natural”. Following established trade routes, viticulture spread from the Black Sea region to the Iberian Peninsula. After the 1st century AD, Italy became the largest wine producer in the Mediterranean, while production flourished in regions known as Gaul and Hispania.

Preservation and Renaissance: The Medieval and Modern Eras

Grape Plantation in Modern Eras

https://roughntoughzindagi56.blogspot.com/2025

Roughntoughzindagi56.blogspot.com

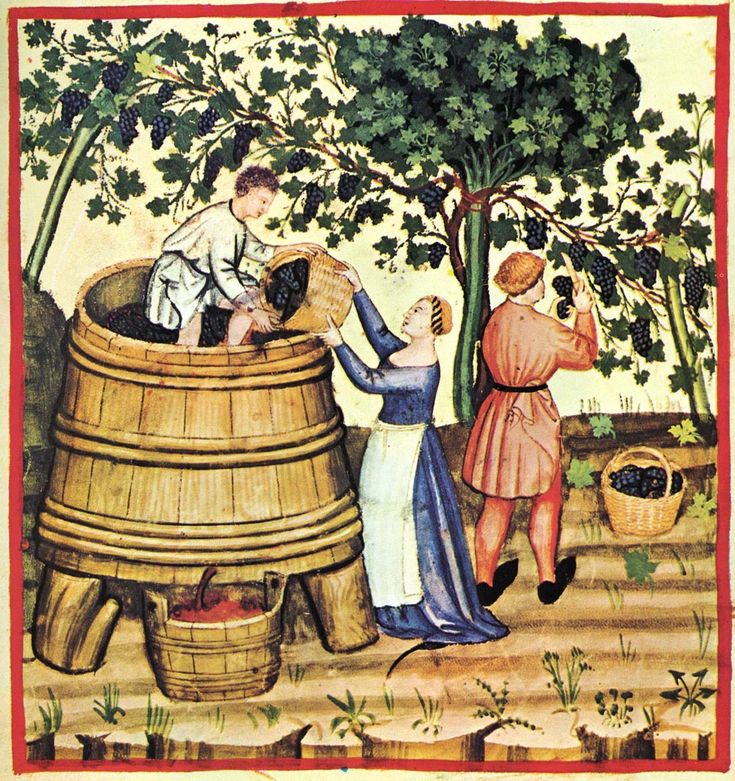

Monastic Orders: Guardians of the Vine and the Birth of Terroir

Following the collapse of the Roman Empire and during the often-troubled Medieval period, the preservation and advancement of viticultural knowledge fell largely to Christian monastic orders, notably the Benedictine and Cistercian monks, especially in regions like Burgundy.

These religious communities enjoyed a certain measure of peace and stability, allowing them to refine and transmit rigorous winegrowing expertise across generations

Their methods covered all phases of production, from pruning and selecting varietals to preservation. The preservation of these complex skills was necessitated by the need for a stable supply of high-quality sacramental wine for the Eucharist.

This religious imperative drove systematic observation over centuries, leading to the establishment of the foundational notions for the identity of the terroir: the delineation of Climats (specific, delimited vineyard sites) and the construction of Clos (walled vineyards built by monks to protect the vines).

The stability of these institutions, combined with detailed written record-keeping, allowed monks to observe and meticulously map the subtle geological and climatic differences between neighboring vineyard plots, a practice that directly anticipated modern quality control and appellation systems.

Furthermore, the rise of these orders and their viticultural success coincided with the Medieval Warm Period (approximately 950 to 1200 AD), where abnormally warm temperatures and low rainfall favored grape ripening, encouraging the geographical expansion of the vine alongside the monks’ missionary efforts.

Global Expansion: The Rise of New World Wine

https://roughntoughzindagi56.blogspot.com/2025/08/italian-wine.html

http://Roughntoughzindagi56.blogspot.com

The Age of Exploration saw the spread of Vitis vinifera outside its traditional European and Middle Eastern homeland, leading to the development of “New World wines” in regions such as the Americas, South Africa, Australia, and New Zealand. This expansion was primarily driven by colonial and missionary requirements.

The need for wine for the Eucharist required missionaries to establish viticulture in new, often hostile, environments. This sacramental imperative provided the crucial, non-commercial impetus necessary to underwrite the difficult early phases of wine production in these colonies.

Over time, economic factors began to drive growth. For instance, in the 1860s, English tariffs on South African wines provided Australia with an opportunity. By the 1900s, Australian wine exports had skyrocketed from 264 hectoliters (HL) to nearly 20,000 HL per annum, though early production centered mainly on fortified wines like Port and Sherry until the 1970s.

Since about 1970, both the quantity and quality of New World wines have increased dramatically, finding significant export success, particularly in non-wine-producing markets like the UK and North America.

The Modern Crisis and Scientific Solution: Phylloxera and Pasteur

The trajectory of wine history was violently reset in the late 19th century by two transformative forces: the biological crisis of Phylloxera vastatrix and the scientific revolution led by Louis Pasteur.

Starting around 1860, a microscopic yellow louse, Phylloxera vastatrix, native to the Mississippi Valley of the eastern United States, was unknowingly introduced to Europe via imported American native vines.

This pest devastated the unprotected roots of European Vitis vinifera. The scale of destruction was catastrophic: by 1878, over 25% of France’s vineyard acreage (915,000 acres killed) was lost, causing French production to decrease by half and turning France into the world’s largest wine importer.

The pest also ravaged Spain, wiping out nearly 99% of Navarra’s vines between 1891 and 1896. Thousands of vintners emigrated, convinced that European winemaking was doomed.

After failed solutions—such as expensive pesticides (carbon disulfide) and unpalatable American hybrids—the final, permanent solution emerged: grafting European Vitis vinifera onto phylloxera-resistant American rootstock.

This technical requirement established the universal blueprint for the modern wine industry, necessitating that almost every vineyard globally now relies on this integrated technical platform.

This crisis was not merely a setback; it was a standardization event that accelerated globalization, forcing experienced French vintners to seek new beginnings in other regions.

The economic instability that resulted, such as France raising aggressive tariffs on Spanish wine upon domestic recovery in 1892 , further underscored the need for international trade management and protection.

Concurrently, a scientific revolution redefined winemaking. In the mid-19th century, French scientist Louis Pasteur, hailed as the father of microbiology, fundamentally changed oenology. He demonstrated that alcoholic fermentation was not a mystical transformation but a biological process conducted primarily by microorganisms, yeasts.

This revelation shifted winemaking from an empirical craft to a predictable, controllable scientific discipline. Furthermore, Pasteur developed pasteurization—heating beverages like wine and milk to kill harmful bacteria. Pasteurization, developed specifically to allow for the export of wine to England , guaranteed shelf stability, making long-distance global trade reliable and providing an essential tool for the recovery of the Old World vineyards and the expansion of the New World.

Defining Quality: The Rise of Appellation Systems

Following the double shock of Phylloxera and the resulting global standardization of rootstock, European producers required a mechanism to protect and differentiate their recovered regional identities. This need led directly to the codification of quality through appellation systems.

France pioneered this effort, creating the Appellation d’Origine Contrôlée/Protégée (AOC/AOP) system in 1935, managed by the Institut National de l’Origine et de la Qualité (INAO).

This system imposed rigorous management on nearly every aspect of wine production, including permissible grape varieties, minimum alcohol levels, and vineyard planting density, applying to over 360 AOCs today.

The AOC structure represents the legal and economic superstructure built upon the foundation of monastic terroir observation (Climats). After Phylloxera forced mass replanting onto a common American rootstock, the AOC system became necessary to legally and economically link the wine’s intrinsic value and price back to the place and tradition (terroir) rather than the now-homogenized plant genetics. Other nations followed suit, such as Italy with its Denominazione di Origine Controllata (DOC) and DOCG systems, often designed to champion indigenous grape varieties.

The history of wine, from its prehistoric origins to its modern global dominance, is synthesized in the timeline below:Global Wine History Timeline (6000 BC – Present)

I’m a professional Astrologer, Numerologist, and Gemologist, and also a passionate lifestyle blogger at CoonteeWorld.com — writing about fashion, travel, wine, horses, and the art of living.